The ISSN’s New Position Stand on Ketogenic Diets: Summary + My Commentary

Some Background

About two weeks ago, the International Society of Sports Nutrition (ISSN) published its first-ever position stand on ketogenic diets [1]. For anyone unfamiliar with the concept of a position stand, it essentially aims to encompass the scientific consensus on a given topic. Position stands – also called position statements – are produced by only a small handful of scientific organizations in the nutrition & exercise space. The ISSN updates their position stands every ten years, so I’m excited to announce that I will be lead-authoring their position stand on diets for bodyweight reduction. The latter will be an update of their position stand on diets & body composition [2], and I will definitely keep you updated about when it drops.

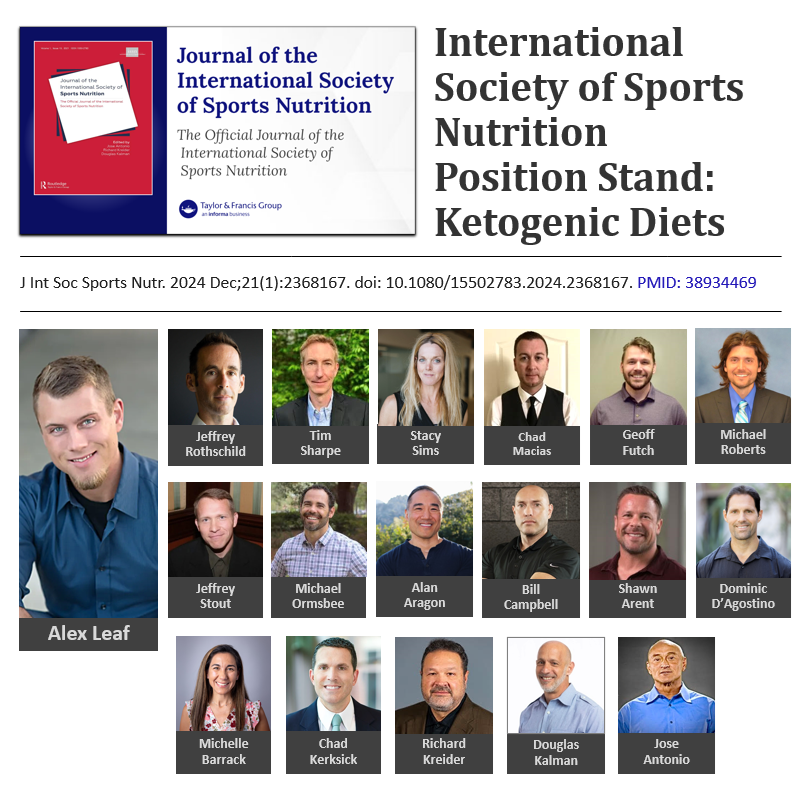

The ISSN position stand on ketogenic diets is a long time coming. It was started before the pandemic, with my friend and colleague Alex Leaf leading the paper. A series of derailments occurred, but then the stars aligned to reboot the project in January of this year, at which point I was included as a co-author. So, I and seventeen other authors ganged up on Alex’s initial draft and picked it apart until we all ran out of things to modify and amend. This process was intense and exhausting, but after a little over half a year, we completed the paper. Take note that we covered ketogenic diets as they apply to body composition and athletic goals. While clinical and health-related effects of ketogenic diets are an interesting area of study, this is outside of the scope of the position stand.

The Position Statements

1. A ketogenic diet induces a state of nutritional ketosis, which is generally defined as serum ketone levels above 0.5 mM. While many factors can impact what amount of daily carbohydrate intake will result in these levels, a broad guideline is a daily dietary carbohydrate intake of less than 50 grams per day.

2. Nutritional ketosis achieved through carbohydrate restriction and a high dietary fat intake is not intrinsically harmful and should not be confused with ketoacidosis, a life-threatening condition most commonly seen in clinical populations and metabolic dysregulation.

3. A ketogenic diet has largely neutral or detrimental effects on athletic performance compared to a diet higher in carbohydrates and lower in fat, despite achieving significantly elevated levels of fat oxidation during exercise (~1.5 g/min).

4. The endurance effects of a ketogenic diet may be influenced by both training status and duration of the dietary intervention, but further research is necessary to elucidate these possibilities. All studies involving elite athletes showed a performance decrement from a ketogenic diet, all lasting six weeks or less. Of the two studies lasting more than six weeks, only one reported a statistically significant benefit of a ketogenic diet.

5.A ketogenic diet tends to have similar effects on maximal strength or strength gains from a resistance training program compared to a diet higher in carbohydrates. However, a minority of studies show superior effects of non-ketogenic comparators.

6. When compared to a diet higher in carbohydrates and lower in fat, a ketogenic diet may cause greater losses in body weight, fat mass, and fat-free mass, but may also heighten losses of lean tissue. However, this is likely due to differences in calorie and protein intake, as well as shifts in fluid balance.

7. There is insufficient evidence to determine if a ketogenic diet affects males and females differently. However, there is a strong mechanistic basis for sex differences to exist in response to a ketogenic diet.

My thoughts on the bangers above

Position statements #1 & 2 are straightforward and uncontentious; they’re rooted in basic/fundamental physiology and biochemistry. The paper has a lengthy and in-depth section on dietary ketogenesis and the role of ketones in exercise bioenergetics.

Position statements #3 & 4 are largely uncontroversial as well, although low-carb/keto absolutists will always be bothered by the idea that low-balling carbohydrate intake could be detrimental to any goal whatsoever. The essence of disagreement and misunderstanding stems from the idea that increased fat oxidation (as a result of becoming “keto-adapted,” also called “fat-adapted”) is always a good thing. However, this actually antagonizes the goal of athletic performance [3]. Becoming fat-adapted occurs alongside becoming carb-impaired. Bear with me on the explanation, which I will try to simplify as much as I can without oversimplifying it. Within a week of carbohydrate restriction combined with high-fat intake, the activity of pyruvate dehydrogenase (an enzyme crucial to glycogen breakdown) decreases [4]. Decreased glycogen breakdown reduces glucose availability and oxidation, which is not a good situation for maximizing athletic performance. This is because compared to fat oxidation, glucose oxidation provides far more ATP per unit of time. In simpler terms, fat is not a good fuel source for athletic performance, particularly in sporting events that involve a mix of intensity levels (most sporting events, including most endurance sports) [5,6].

Position statement #5 on the surface seems to give a pass to ketogenic diets for strength gain. However, keto is still a gamble for individuals with competitive goals, or for individuals seeking to maximize/optimize strength gains). The current body of studies has important caveats to consider. Quoting the position stand: “Caution is warranted since a minority of studies indeed show superior effects of the higher-carbohydrate comparator for improving or retaining strength performance. Furthermore, there is a lack of trials exceeding 12 weeks involving highly trained strength athletes. Cautious monitoring of individual response is recommended for strength athletes choosing a ketogenic diet, due to its potential to suboptimize training adaptations in the long-term.”

Unfortunately, it’s common for studies on this topic to fail to equate protein intake. The keto groups often consume substantially more protein than the control groups, thus reaping the advantages thereof. Not only does higher protein impart benefits to strength performance, it also gives the advantage to the keto in terms of body composition improvements (particularly with bodyweight and fat loss due to greater satiety). This treatment imbalance within studies explains the conclusions drawn in position statement #6. When protein and calories are rigorously controlled (equated between the groups) in diet comparisons, there’s no significant fat loss advantage of keto diets versus the high-carb control diets [2]. Ketogenic diets are also suboptimal for the goal of increasing muscle mass, particularly in resistance-trained subjects [7,8]. Just to be clear for the keto diehards – it’s still possible to gain muscle on keto. However, ketogenic diets are inefficient for this goal, and rates of gain (as well as hypertrophic potential) are not likely to be maximized.

Position statement #7 pertains to an interesting area of study (sex-based differences in response to ketogenic diets). Although substrate utilization differences exist, there is a lack of research directly comparing exercise performance and body composition effects of a ketogenic diet in men versus women. Therefore, no definitive conclusions or practical implications can be drawn until future investigations provide further insights.

For those interested and tenacious enough to make the journey through about 10,000 words, here is the free full text of the position stand. Happy reading!

_________________________________________________

Alan Aragon is the Chief Science Officer of the Nutritional Coaching Institute. With over 30 years of success in the field, he is known as one of the most influential figures in the fitness industry’s movement towards evidence-based information. Alan has numerous peer reviewed publications that continue to shape the practice guidelines of professionals, and the results of their clientele. He is the founder and Editor-In-Chief of Alan Aragon’s Research Review (AARR), the original and longest-running research review publication in the fitness industry.

Alan Aragon is the Chief Science Officer of the Nutritional Coaching Institute. With over 30 years of success in the field, he is known as one of the most influential figures in the fitness industry’s movement towards evidence-based information. Alan has numerous peer reviewed publications that continue to shape the practice guidelines of professionals, and the results of their clientele. He is the founder and Editor-In-Chief of Alan Aragon’s Research Review (AARR), the original and longest-running research review publication in the fitness industry.

References

- Leaf A, Rothschild JA, Sharpe TM, Sims ST, Macias CJ, Futch GG, Roberts MD, Stout JR, Ormsbee MJ, Aragon AA, Campbell BI, Arent SM, D’Agostino DP, Barrack MT, Kerksick CM, Kreider RB, Kalman DS, Antonio J. International society of sports nutrition position stand: ketogenic diets. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2024 Dec;21(1):2368167.

- Aragon AA, Schoenfeld BJ, Wildman R, Kleiner S, VanDusseldorp T, Taylor L, Earnest CP, Arciero PJ, Wilborn C, Kalman DS, Stout JR, Willoughby DS, Campbell B, Arent SM, Bannock L, Smith-Ryan AE, Antonio J. International society of sports nutrition position stand: diets and body composition. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2017 Jun 14;14:16.

- Burke LM, Sharma AP, Heikura IA, Forbes SF, Holloway M, McKay AKA, Bone JL, Leckey JJ, Welvaert M, Ross ML. Crisis of confidence averted: Impairment of exercise economy and performance in elite race walkers by ketogenic low carbohydrate, high fat (LCHF) diet is reproducible.

- Stellingwerff T, Spriet LL, Watt MJ, Kimber NE, Hargreaves M, Hawley JA, Burke LM. Decreased PDH activation and glycogenolysis during exercise following fat adaptation with carbohydrate restoration. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Feb;290(2):E380-8.

- Burke LM, Whitfield J. Ketogenic diets are Not Beneficial for Athletic Performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2024 Apr 1;56(4):756-759.

- Burke LM. Re-examining high-fat diets for Sports Performance: Did We Call the ‘Nail in the Coffin’ Too Soon? Sports Med. 2015 Nov;45 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S33-49.

- Vargas-Molina S, Petro JL, Romance R, Kreider RB, Schoenfeld BJ, Bonilla DA, Benítez-Porres J. Effects of a ketogenic diet on body composition and strength in trained women. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2020 Apr 10;17(1):19.

- Vargas S, Romance R, Petro JL, Bonilla DA, Galancho I, Espinar S, Kreider RB, Benítez-Porres J. Efficacy of ketogenic diet on body composition during resistance training in trained men: a randomized controlled trial. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2018 Jul 9;15(1):31.